Chzan CHIAN – Independent analyst and researcher

In June, 2012 the People's Bank of China set the benchmark lending rate at 6%, sending a clear message that Beijing was switching to much stronger economy stimulation policies in a bid to boost growth.

Start of a New Cycle

The Chinese administration unveiled an unprecedented stimuli package back in the fall of 2008 in an attempt to shield China from the crisis which started to spill across the Western economies. The liquidity injection which followed eventually drove up inflation and caused the overheated Chinese economy to cool down.

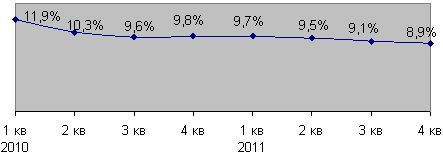

Fig. 1. GDP growth in 2010-2011

In February 25, 2010 the People's Bank of China imposed tighter capital requirements on commercial banks and thus marked the starting point of the cooling cycle. Restrictive monetary policies were expanded in the fall of 2010 to apply to the interest rates which were upped from 5.31% to 5.56%1. Three more hikes were announced later on, the last one – in June, 2011 (Table 1). The interest rate stayed unchanged throughout the second half of 2011, and by the end of the year the People's Bank of China pressed a lower figure as the GDP growth continued to slow down and the decision was made in favor of cautiously stimulating the economy.

As of 2011, surveys offered both an alarming picture of the state of the global market and a vivid account of China's swelling socioeconomic problems. Reports highlighted asynchronism and imbalances across the Chinese economy along with “intolerable” disproportions, and called for faster structural adjustments2.

Table 1.

Lending and deposit rates in China

|

Date enacted |

One-year lending rate |

One-year deposit rate |

Housing credit rate* |

|

16.09.2008 |

7.20 |

4.14 |

4.05 |

|

09.10.2008 |

6.93 |

3.87 |

4.05 |

|

30.10.2008 |

6.66 |

3.60 |

4.05 |

|

27.11.2008 |

5.58 |

2.52 |

3.51 |

|

23.12.2008 |

5.31 |

2.25 |

3.33 |

|

20.10.2010 |

5.56 |

2.50 |

– |

|

26.12.2010 |

5.81 |

2.75 |

3.75 |

|

08.02.2011 |

6.06 |

3.00 |

– |

|

07.07.2011 |

6.56 |

3.50 |

4.45 |

|

07.06.2012 |

6.31 |

3.25 |

– |

|

04.07.2012 |

6.00 |

3.00 |

– |

* For terms up to 5 years. Source: China People's Bank (pbc.gov.cn)

It should be noted that the economic growth in China dropped off smoothly throughout 2011, measuring 9.7% in the first quarter, 9.5% – in the second, 9.1% – in the third, and 8.9% in the fourth. It averaged 9.2% on the annualized basis, which was 1.2% below the 2010 result. The 4% inflation target was not reached – over the year, consumer prices added 5.4%, with the indicator peaking to 6.5% in July and rolling back to 4.1% in December. Food prices, in particular, rose by 11.8%.

The growth in 2012 – 8.1% in the first and 7.6% in the second quarter – continued to lose momentum, but the efforts to curb inflation over the six months met with considerable success. The annualized CPI (Consumer Price Index) was recorded at 2.2% (3.8% for foodstuffs), and the consumer prices over the six months increased only by 3.3%. During the same period of time, the PPI (Producer Price Index) shed 0.6% relative to the first six months of 2011. In June, 2012, it was 2.1% below the June, 2011 mark.

Soft Landing

Importantly, tamed inflation is regarded in China as the key evidence of the economy's soft landing. Actually, the very term can be traced back to the 1993-1996 anti-inflation campaign. The 1992 commodities and tariffs deregulation sent the Chinese economy deep into inflationary territory. The release of grain prices from government control in over 400 districts by the end of 1992 further fueled the outbreak. The industrial equipment price index jumped by 33.1% by the end of 1993. Problems piled up dramatically as more grain pricing deregulation followed and the 1994 harvest proved poor: at the time, the annualized foodstuffs prices growth spiked to 48.3% for grain, 35.6% for meat, poultry, and eggs, and 30.8% for vegetables. Since the moment and throughout 1995, the Chinese government played rough against the inflation, drawing in all available resources. In fact, the anti-inflation measures trickled down to the micro-regulation level, while the government did not shy away from directly employing administrative leverage.

Inflation was finally reigned in in 1996, the year seen in China as the time of the economy's soft landing (the Zhū Róngjī soft landing, by the name of the then-premier of China). It marked a normal completion of the reform cycle and the opening of the 1997-2005 epoch of healthy economic development with reasonable inflation levels and a stable yuan exchange rate. In the settings, China implemented a far-reaching reform of state-run companies and banks and put them seriously on track in terms of efficiency and competitiveness.

The 1996 stabilization in China became a prologue to widening liberalization and greater openness of the economy. For example, already in 1996 Beijing started to selectively admit foreign financial institutions to the sphere of yuan transactions, though the experimental character of the corresponding arrangements and the lack of conditions for expanding the practice regionally, least on the nationwide scale, were stated in all cases.

China's demonstrated ability not to crack under pressure exerted by the 1997-1998 Asian crisis reinforced the credibility of Beijing's course which implied gradualism and caution with regard to lifting the financial quarantine, the government's steady grip on currency affairs and financial flows, and the treatment of portfolio investments with permanent suspicion. Divestment prevention and measured insulation of national manufacturers, banks, and insurers against the international competition combined into the underpinning of China's economic policies when, in 1999-2001, the country was bracing to blend into the WTO.

At the moment, there are strong indications that the inflation reduction achieved in China by the summer of 2012 signaled the country's readiness for the new cycle during which the economy is to be re-energized with the help of fiscal stimuli. It should be taken into account in the context that the previous, relatively soft stimulation did not cause the M2 index to climb unchecked: it stayed at 13.6% – the level of late 2011 – in the first half of 2011 and grew by 0.4% in June compared to May.

Causes for Concern

It is an open secret that a fraction of the financial package dished out in 2009 was diverted to the speculative sector, a side-effect being the sky-rocketing of the urban housing prices. Housing sales posted sluggish growth in 2011 due to the above, putting on 12.1% in terms of costs and only 4.9% in volume.

Table 2.

New housing prices dynamics in cities in December, 2011 vs. December, 2010

|

City |

Price, % |

City |

Price, % |

|

Beijing |

101.0 |

Jilin |

101.9 |

|

Shanghai |

101.8 |

Chongqing |

99.4 |

|

Tianjin |

101.2 |

Sanya |

100.9 |

|

Shenzhen |

103.1 |

Taiyuan |

101.2 |

|

Guangzhou |

103.1 |

Shenyang |

102.4 |

|

Hangzhou |

101.0 |

Haerbin |

100.2 |

|

Nanjing |

99.7 |

Lanzhou |

101.7 |

|

Ningbo |

98.8 |

Xi'an |

103.4 |

|

Dalian |

102.2 |

Wulumuqi |

105.5 |

Source: based on the data supplied by the State Statistic Agency (stats.gov.cn)

The 2011 data on real estate sales in China's eastern provinces which account for 60% of the nationwide market came as bad news. Expressed in the current prices, the growth stalled at 3.8%, a figure which clearly reflects a downward trend.

The situation further deteriorated in the first quarter of 2012 as the housing sales volume shrank by 14.3%, a poor show compared to the first quarter of 2011 when it grew by 14.3% in the first quarter. Even that, however, was better than the critical 30% contraction reported in 2008.

The downward pricing tendency on the real estate market also persisted into the first quarter of 2012, but the developments stopped short of a full-blown collapse, especially considering that the lower prices generally agreed with the regulator's planning. A comparison against the 2010 prices shows that the prices went down only in five cities – Nanjing, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Wenzhou, and Nanchong – and, with the exception of the affluent Wenzhou, the slide was fairly moderate. Moreover, a slight recovery ensued in the second quarter of 2012 as the contraction of the real estate sales over a half of the year turned out to be 10.7%, which was much less than in 2011.

It may yet transpire that the problems confronting the sector as a whole are overstated. The regulator meant to cool the market and to cap the prices, both tasks being, to an extent, accomplished, plus the sales appear to be rebounding. In any case, the situation in China cannot be approached with the criteria appropriate for the US. The US saw real estate prices sink by a little more than 6%, but roughly a half of the US GDP is linked to this part of the market, whereas the role of real estate within the Chinese investment model is much narrower. Mortgages in China still sum up to a modest total3, the population's savings keep growing fast4, and the sector likely acquires a better balanced configuration as the prices enter a plateau.

Certain concerns arise in connection with the provincial governments' indebtedness which is mostly attributable to the construction of new infrastructures. Premier Wen Jiabao addressed the above issues at the March, 2012 session of the National People's Congress. He said that the administration persistently tightened control over the real estate market and gauged the practical efficiency of the policy, reining in investors and speculators, and the prices started to go down in the majority of Chinese cities. Wen Jiabao also explained that major efforts were made to eliminate or avoid risks in the monetary sphere and to monitor the local governments' indebtedness levels. Full information was collected concerning the amounts owed, the corresponding terms, as well as the regional distribution and origins of the debts. According to the Chinese premier, the debts in a way helped the country's socioeconomic development and altogether morphed into a massive group of quality assets, but some problems can arise, mostly on the local level in the regions which might have difficulty repaying them5.

A range of options are open to handle the aforementioned quality assets, and the central government has no shortage of reserves to throw in to ward off crises. State revenues mounted in China over the recent years even faster than the GDP, economically empowering the government against potential threats6.

Safety Pillow

While the Chinese economy is routinely described as export-driven, the country's drift towards the reliance on domestic demand, a stronger service-oriented sector, and a healthier socioeconomic climate is impossible to deny. China maintained convincing growth even as it stormed through the 2009 global trade downturn, prompting a number of commentators to conclude that the impact of external factors on the Chinese economy is not as high as widely believed7. For example, China is less dependent on energy imports than most other economic powerhouses.

Chances are, though, that deepening the domestic market and expanding native demand in China would take many a bold step on top of upgrading the national infrastructures. Speaking of the infrastructures, China already made significant leaps forward in the area, though a few gross failures, as in operating rapid rail transit, did occur in the process.

The degree of transition to the economic model powered by domestic demand and a bigger service sector, including the financial one, varies widely in China from province to province. The more successful, mostly coastal provinces are also the ones boasting social gaps not as wide as the inland ones, meaning that the overall conventional growth remains a prime necessity for the country in the evolving economic context. Consequently, the Chinese economy will not dispense with a subset of its key traits8 while the investment priorities will change and increasingly gravitate towards advanced technologies, clean energy, financial infrastructures, and heavier urbanization. The country will still need heightened accumulation rates and intensity of investments to prop up broad construction activity, to modernize industrial assets, and to directly and indirectly create jobs. That, in turn, implies that the national investment policies will, as before, be championed in China by the state-run sector and banks, which, at the moment, are in a decent shape for the mission.

China counted somewhat over a hundred centrally run enterprises by the end of 2011 (196 apart from banks in 2003). Reportedly, the summary assets of the ecosystem weighted 26 trillion yuan (8.4 trillion yuan in 2003). The state-run sector, central and provincial, posted gains in the amount of 2,257 billion yuan – a 12.8% revenue increase – in 2011, accounting for a third of the budget revenues, 14% of the national export, and 28% of the import. The state sector contributes 48-50% of the investments in China, beefing up the share at the phases when the private sector stumbles. Most of the credits issued by big state-run Chinese banks land in similarly big state-run enterprises.

The revenues of Chinese commercial banks in 2011 topped 1 trillion yuan in 2011, adding 36.3% (compared to the 34.5% growth in 2010). As a parallel development, the capital sufficiency level in the banking sector rose from 12.2% to 12.7%. The private sector in a number of Chinese coastal provinces currently faces far more serious problems than the state sector due to being essentially export-oriented. Aware of the situation, the government intervened in the forms of offering direct state-bank lending to private companies and licensing formerly unauthorized types of activities to private banks.

Quite a few analysts suspect that the Chinese banking sector may be loaded with toxic assets dating back to the 2009-2010 credit boom, but, on the other hand, China should feel secure as it sits on impressive currency reserves, owes remarkably little internationally, and has a domestic debt equal to just 27% of the GDP.

The policy of cooling the Chinese economy which overheated upon absorbing the 2009 anti-crisis package produced appreciable results in 2011, though the disproportions far from evaporated. Judging by the available data, the Chinese economy should be stable in 2012, and the country's leadership will likely focus on preventing the economic growth from stalling. Overall, China seems to be confidently en route to a soft landing.

1. For the first time ever, the step drew a negative reaction from the financial markets, which read as a de facto recognition of China's global economic status

2. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjgb/ndtjgb/qgndtjgb/t20120222_402786440.htm

3. Consumer credits in China total 6 trillion yuan, or roughly a quarter of the population's savings

4. They went up by 12.6% in February, 2012

5. http://russian.china.org.cn/exclusive/txt/2012-03/14/content_24896428_3.htm

6. For example, in 2011 the budget revenues rose by 24.8% and broke the 10.3 trillion yuan mark (22% of the GDP)

7. Zhang Wenlang, Dong He. How Dependent is the Chinese Economy of Exports and in What Sense Has Its Growth Been Export Led?// Journal of Asian Economics. 2010. Issue 21.

8. In March, 2009, China Daily featured two opinion pieces by People's Bank of China governor Zhou Xiaochuan, which offered a sharply critical perspective on the existing global financial architecture and praised East Asia's typical high accumulation rates as a reasonable alternative to the debt-driven US economy. Premier Wen Jiabao also spoke about the need to balance consumption and accumulation in Davos in 2009.